THE BIOGRAPHY OF IVO ANDRIĆ

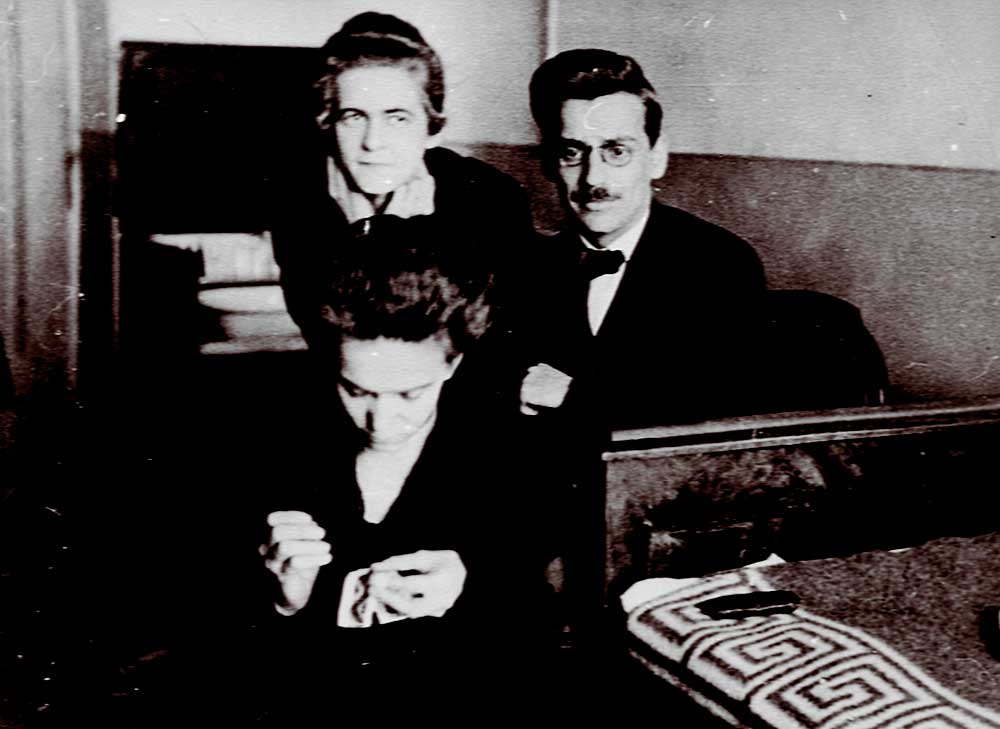

On October 9, 1892, the birth of Ivan, son of Antun Andrić, custodian, and Katarina Andrić, nee Pejić, was noted under entry number 70 in the Register of Births kept in the Church of St. John the Baptist in Travnik. The future great Serbian writer was born in Travnik by happenstance, during his mother’s visit to her relatives. Ivo Andrić’s parents were from Sarajevo: his father’s family had been established in the town for decades, engaged in the brass working trade. In addition to working in the same trade, members of the Andrić family were linked by the same ill fate of tuberculosis: many of the writer’s ancestors, including all his father’s brothers, succumbed in their youth, and Andrić himself lost his father when he was two years old. Faced with penury, Katarina Andrić took her only child to be raised by her husband’s sister Ana and Ana’s husband Ivan Matkovščik in Višegrad. Andrić completed elementary school in this town which was to mark his creativity more than any other place, gazing daily at the slender arches of the bridge over the

On October 9, 1892, the birth of Ivan, son of Antun Andrić, custodian, and Katarina Andrić, nee Pejić, was noted under entry number 70 in the Register of Births kept in the Church of St. John the Baptist in Travnik. The future great Serbian writer was born in Travnik by happenstance, during his mother’s visit to her relatives. Ivo Andrić’s parents were from Sarajevo: his father’s family had been established in the town for decades, engaged in the brass working trade. In addition to working in the same trade, members of the Andrić family were linked by the same ill fate of tuberculosis: many of the writer’s ancestors, including all his father’s brothers, succumbed in their youth, and Andrić himself lost his father when he was two years old. Faced with penury, Katarina Andrić took her only child to be raised by her husband’s sister Ana and Ana’s husband Ivan Matkovščik in Višegrad. Andrić completed elementary school in this town which was to mark his creativity more than any other place, gazing daily at the slender arches of the bridge over the Drina River; then he returned to his mother in Sarajevo. In 1903 he enrolled in the Sarajevo Grammar School, the oldest secondary school in Bosnia and Herzegovina. During his secondary school days Andrić began to write poetry and in 1911 the Bosanska vila (Bosnian Fairy) published his first poem, “U sumrak” (At Twilight). As a secondary school student, Andrić was a fierce advocate of the YugSarajevooslav cause, a member of the progressive nationalistic movement “Mlada Bosna” (Young Bosnia) and a zealous fighter for the liberation of the South Slav peoples from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Drina River; then he returned to his mother in Sarajevo. In 1903 he enrolled in the Sarajevo Grammar School, the oldest secondary school in Bosnia and Herzegovina. During his secondary school days Andrić began to write poetry and in 1911 the Bosanska vila (Bosnian Fairy) published his first poem, “U sumrak” (At Twilight). As a secondary school student, Andrić was a fierce advocate of the YugSarajevooslav cause, a member of the progressive nationalistic movement “Mlada Bosna” (Young Bosnia) and a zealous fighter for the liberation of the South Slav peoples from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

After having received a scholarship from “Napredak”, the Croatian cultural-educational society, in October 1912 Andrić began his studies at the Royal University in Zagreb. In this town on the Sava River, he studied a bit, visited salons a bit, and socialized with the Zagreb intelligentsia; the writer Antun Gustav Matoš, twenty years his senior, had the greatest influence on him. The next year he moved to Vienna where he attended lectures in history, philosophy and literature. The weather in 1912.Vienna did not agree with him; owing to his hereditary burden of sensitive lungs he often suffered from pneumonia. Turning to his secondary school professor and benefactor Tugomir Alaupović for help, the next year he went to the Faculty of Philosophy of Jagiellonian University in

After having received a scholarship from “Napredak”, the Croatian cultural-educational society, in October 1912 Andrić began his studies at the Royal University in Zagreb. In this town on the Sava River, he studied a bit, visited salons a bit, and socialized with the Zagreb intelligentsia; the writer Antun Gustav Matoš, twenty years his senior, had the greatest influence on him. The next year he moved to Vienna where he attended lectures in history, philosophy and literature. The weather in 1912.Vienna did not agree with him; owing to his hereditary burden of sensitive lungs he often suffered from pneumonia. Turning to his secondary school professor and benefactor Tugomir Alaupović for help, the next year he went to the Faculty of Philosophy of Jagiellonian University in  Cracow. He studied the Polish language intensively, became acquainted with the local culture and attended lectures by excellent professors. All this while he was writing reflective prose poems, and in June 1914 the Croatian Writers Society in Zagreb published six of his prose poems in the anthology Hrvatska mlada lirika (Young Croatian Lyricists).

Cracow. He studied the Polish language intensively, became acquainted with the local culture and attended lectures by excellent professors. All this while he was writing reflective prose poems, and in June 1914 the Croatian Writers Society in Zagreb published six of his prose poems in the anthology Hrvatska mlada lirika (Young Croatian Lyricists).

On St. Vitus’ Day, June 28, 1915.1914, at news of the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand in Sarajevo, Andrić packed his meager student’s suitcases and left Krakow: the pernicious instinct of the former revolutionary forced him to return home, to the stage of history. As soon as he arrived in Split in mid-July, the Austrian police arrested him and took him to prison, first in Šibenik and then in Maribor where he remained a political prisoner until March 1915. Between the walls of the Maribor prison, in the darkness of solitary confinement, “humiliated like vermin”, Andrić intensively wrote his prose poems.

On St. Vitus’ Day, June 28, 1915.1914, at news of the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand in Sarajevo, Andrić packed his meager student’s suitcases and left Krakow: the pernicious instinct of the former revolutionary forced him to return home, to the stage of history. As soon as he arrived in Split in mid-July, the Austrian police arrested him and took him to prison, first in Šibenik and then in Maribor where he remained a political prisoner until March 1915. Between the walls of the Maribor prison, in the darkness of solitary confinement, “humiliated like vermin”, Andrić intensively wrote his prose poems.

Upon being released from prison, Andrić was confined to Ovčarevo and Zenica where he remained until the summer of 1917. Owing to a relapse of his lung disease, he set out at once to be treated in Zagreb at the famous Hospital of the Sisters of Charity where the Croatian intelligentsia had avoided taking part in the war on Austria’s side. Andrić, together with Count Ivo Vojnović, was there when the general amnesty was proclaimed and actively participated in preparations for the first issue of the journal Književni jug (Literary South). At the same time he was putting the finishing touches on his book of prose poems entitled Ex Ponto that was to be published in Zagreb in 1918 with a preface by Niko Bartulović. He was also in Zagreb when the Austro-Hungarian monarchy collapsed, which was followed by unification and the creation of the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. In the days that immediately preceded formal unification, Andrić in his text “Nezvani neka šute” (Let the Unconcerned Keep Still) published in the Zagreb daily Novosti, critically responded to the first signs of disagreement in a country that had not even been created, calling for unity and reason.

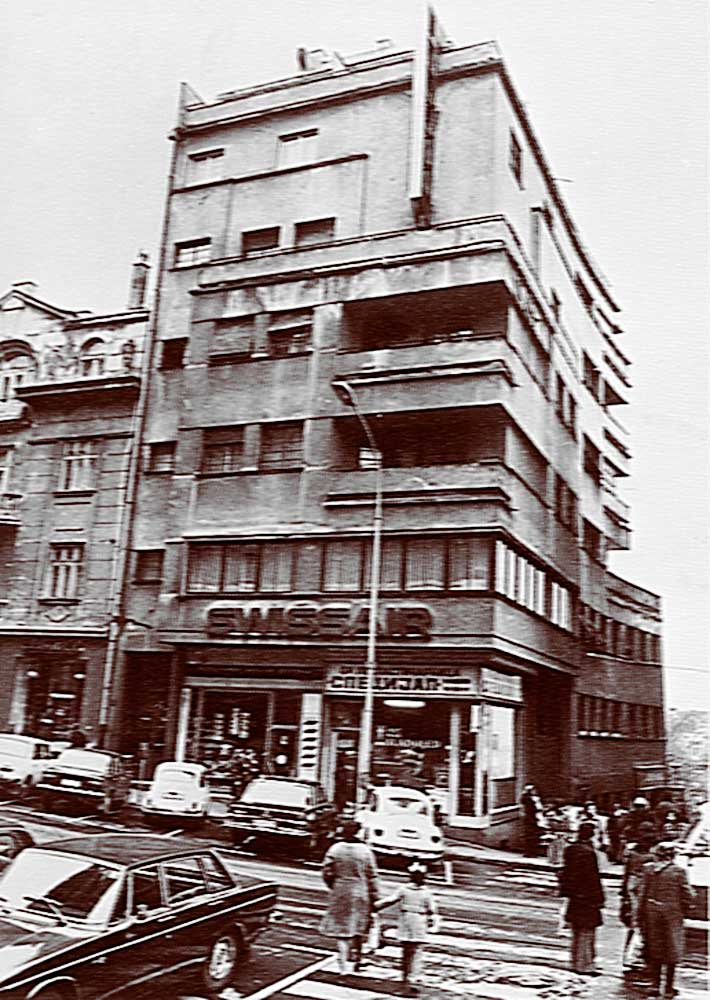

Dissatisfied with the atmosphere in Zagreb, Andrić once again asked Dr. Tugomir Alaupović for help; at the beginning of October 1919 he began to work as a civil servant in Rome, 1920. Ministry of Religion in Belgrade. Judging by the letters he wrote to his friends, Belgrade gave him a warm welcome and he actively participated in the literary life of the capital city, spending time with Crnjanski, Vinaver, Pandurović, Sibe Miličić and other writers who gathered together at the Moskva café. At the beginning of 1920, Andrić began a very successful diplomatic career with his appointment to the Legation at the Vatican. That year the Zagreb publisher Kugli published a new collection of prose poems entitled Nemiri (Unrest), and the publisher S. B. Cvijanović from Belgrade printed his short story “Put Alije Djerzeleza” (The Journey of Ali Djerzelez).

Dissatisfied with the atmosphere in Zagreb, Andrić once again asked Dr. Tugomir Alaupović for help; at the beginning of October 1919 he began to work as a civil servant in Rome, 1920. Ministry of Religion in Belgrade. Judging by the letters he wrote to his friends, Belgrade gave him a warm welcome and he actively participated in the literary life of the capital city, spending time with Crnjanski, Vinaver, Pandurović, Sibe Miličić and other writers who gathered together at the Moskva café. At the beginning of 1920, Andrić began a very successful diplomatic career with his appointment to the Legation at the Vatican. That year the Zagreb publisher Kugli published a new collection of prose poems entitled Nemiri (Unrest), and the publisher S. B. Cvijanović from Belgrade printed his short story “Put Alije Djerzeleza” (The Journey of Ali Djerzelez).

In the fall of 1921 Andrić was appointed to the General Consulate of the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in Bucharest, 1922.Bucharest, and the same year he began to work with Srpski književni glasnik (Serbian Literary Gazette), publishing in issue 8 the story “Ćorkan i Švabica”. In 1922 he was transferred to the Consulate in Trieste. That year he published: two more short stories “Za logorovanja” (In the Camp) and “Žena od slonove kosti” (“Woman of Ivory”), a cycle of poems “Šta sanjam i šta mi se događa” (What I dream and What Happens To Me), and several literary reviews. At the beginning of 1923 he was appointed vice consul in Graz. Since he had not completed his university studies, he was threatened with losing his job at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Offered the choice of finishing his studies with a state examination or defending a doctorate, Andrić chose the latter and in the fall of 1923 enrolled at the Faculty of Philosophy in Graz. That year Andrić published several short stories, some of which are among his most important works of prose: “Mustafa Madjar” (Mustafa Magyar), “Ljubav u kasabi” (Love in a Small Town), “U musafirhani” (In the Guest-House) and “Dan u Rimu” (Day in Rome). He defended his doctoral thesis The Development of Spiritual Life in Bosnia Under the Influence of Turkish Rule in June 1924 in Graz. On September 15, after defending his doctorate, he received the right to return to diplomatic service. At the end of the year he was transferred to Belgrade to the Political Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. That year his first collection of short stories appeared, published by Srpska književna zadruga (Serbian Literary Association) that included some new stories – “U zindanu” (In Prison) and “Rzavski bregovi” – in addition to other stories that had been previously published in magazines. At the recommendation of Bogdan Popović and Slobodan Jovanović, Ivo Andrić became a member of the Serbian Academy of Science and Art in 1926, and the same year the Serbian Literary Gazette published his stories “Mara milosnica” (The Pasha's Concubine) and “Čudo u Olovu” (Miracle in Olovo). The bridge on the @epa riverIn October he was appointed vice consul of the General Consulate of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Marseilles. The next year he spent three months working in the General Consulate in Paris; Andrić spent almost all his free time in Paris at the National Library and the Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, studying historical material on Bosnia from the beginning of the 19th century and reading the correspondence of Pierre David, the French consul in Travnik. In the spring of 1928 he was appointed vice consul at the Legation in Madrid. That year he published the stories “Olujaci”, “Ispovijed” (Confession) and “Most na Žepi” (Bridge on the Žepa). In the middle of the next year he moved to Brussels to the position of secretary of the legation, and the Serbian Literary Gazette published his essay “Goya”. On January 1, 1930 he began to work in Geneva as the secretary of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia’s permanent delegation to the League of Nations. That year he published an essay on Simon Bolivar and a second book of short stories with the Serbian Literary Association in which earlier published stories were joined by “Anikina vremena” (Anika’s Times), printed in full for the first time. That same year the calendar-almanac of Sarajevo’s Prosvjeta published his travel story “Portugal, zelena zemlja” (Portugal, Land of Green). In 1932 Andrić published the short stories “Smrt u Sinanovoj tekiji” (Death in Sinan’s Tekke), “Na lađi” (On the Boat) and the text “Leteći nad morem” (Flying Above the Sea). In March 1933 he returned to Belgrade as an advisor at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Although writing intensively, that year he only published the short story “Napast” (Temptation) and several texts. On November 14 that same year he replied to Dr. Mihovil Kombol in writing, refusing to allow his poems to be included in Antologija novije hrvatske lirike  (Anthology of Recent Croatian Lyricists): “I could never be part of a publication that would, as a matter of principle, exclude other poets of ours who are similar to myself just because they are of another faith or were born in another province. This is not a recently acquired belief but dates from my early youth, and now in my mature years the basis upon which I make my evaluations will not change”. The next year he was promoted to advisor of the fourth group of the second degree in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He became editor of the Serbian Literary Gazette and published the short stories “Olujaci”, “Žeđ” (Thirst) and the first part of the triptych “Jelena, žena koje nema” (Jelena, the Woman of My Dream). He became head of the political department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1935 and lived at the Excelsior Hotel. That year he published the short stories “Bajron u Sintri” (Byron in Sintra) and “Deca” (Children), the essay “Razgovor s Gojom” (Conversation with Goya) and one of his most important literary texts – “Njegoš kao tragični junak kosovske misli” (Njegoš as Tragic Hero of the Kosovo Idea). The Serbian Literary Association printed a second book of Andrić’s short stories the following year; along with others that had been previously published in magazines, it included the stories “Mila i Prelac” and “Svadba” (The Wedding). Andrić’s diplomatic career was on the rise and in November 1937 he was appointed deputy minister of foreign affairs. That year he received high state decorations from Poland and France: the Order of the Great Commander of Restored Poland and the Order of the Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor. Although occupied with diplomatic duties, that year Andrić published the stories “Trup” (Torso) and “Likovi” (Characters). He also went to Vienna and gathered material in the State Archive about the consulate period in Travnik, studying the reports of Austrian consuls in Travnik from 1808 to 1817 – Paul von Mittesser and Jakob von Paulich. At the beginning of 1938 the first monograph about Andrić appeared, written by Dr. Nikola Mirković.

(Anthology of Recent Croatian Lyricists): “I could never be part of a publication that would, as a matter of principle, exclude other poets of ours who are similar to myself just because they are of another faith or were born in another province. This is not a recently acquired belief but dates from my early youth, and now in my mature years the basis upon which I make my evaluations will not change”. The next year he was promoted to advisor of the fourth group of the second degree in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He became editor of the Serbian Literary Gazette and published the short stories “Olujaci”, “Žeđ” (Thirst) and the first part of the triptych “Jelena, žena koje nema” (Jelena, the Woman of My Dream). He became head of the political department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1935 and lived at the Excelsior Hotel. That year he published the short stories “Bajron u Sintri” (Byron in Sintra) and “Deca” (Children), the essay “Razgovor s Gojom” (Conversation with Goya) and one of his most important literary texts – “Njegoš kao tragični junak kosovske misli” (Njegoš as Tragic Hero of the Kosovo Idea). The Serbian Literary Association printed a second book of Andrić’s short stories the following year; along with others that had been previously published in magazines, it included the stories “Mila i Prelac” and “Svadba” (The Wedding). Andrić’s diplomatic career was on the rise and in November 1937 he was appointed deputy minister of foreign affairs. That year he received high state decorations from Poland and France: the Order of the Great Commander of Restored Poland and the Order of the Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor. Although occupied with diplomatic duties, that year Andrić published the stories “Trup” (Torso) and “Likovi” (Characters). He also went to Vienna and gathered material in the State Archive about the consulate period in Travnik, studying the reports of Austrian consuls in Travnik from 1808 to 1817 – Paul von Mittesser and Jakob von Paulich. At the beginning of 1938 the first monograph about Andrić appeared, written by Dr. Nikola Mirković.

Ivo Andrić’s diplomatic career reached its highpoint in 1939: a communiqué was given on April 1 announcing that Ivo Andrić had been appointed minister plenipotentiary and envoy extraordinary to Berlin. Andrić arrived in Berlin on April 12, and on April 19 presented his credentials to the chancellor of the Reich – Adolph Hitler. In the fall, after the Germans had occupied Poland and sent many scholars and writers to concentration camps, Andrić interceded before the German authorities to save many of them from imprisonment. Politicians in Belgrade, however, did not always count on their envoy, and many contacts were maintained with German authorities that bypassed Andrić. In spite of such circumstance, the writer published: the short story “Čaša” (Glass) and the texts “Staze” (Paths) and “Vino” (Wine) in the Serbian Literary Gazette during 1940. In early spring 1941, Andrić submitted his resignation to the authorities in Belgrade: “…Today I am obliged, above all by many official and personal reasons, to request that I be relieved of these duties and recalled from my current post as soon as possible…” His request was not granted and on March 25 he was present at the signing of the Tripartite Pact in Vienna as the official representative of Yugoslavia. The day after Belgrade was bombed by Germany, April 7, Andrić left Berlin with the other Legation staff. After rejecting the German authorities’ offer to go to the safety of Switzerland, but without the other members of the legation and their families, he chose to return to occupied Belgrade. In November he retired from the diplomatic service but refused to receive a pension. He lived a reclusive life on Prizrenska Street, renting a room from lawyer Brana Milenković. He refused to sign the Appeal to the Serbian people that condemned resistance to the occupying forces. He also refused to let the Serbian Literary Association publish his short stories while “the people are suffering and dying”. In the quiet of his rented room he first wrote Travnička hronika (The Bosnian Story), and then at the end of 1944 completed Na Drini ćuprija (Bridge on the Drina). Both novels were to be published in Belgrade several months after the end of the war, and his novel Gospođica (The Woman from Sarajevo) was published at the end of 1945 in Sarajevo.

Ivo Andrić’s diplomatic career reached its highpoint in 1939: a communiqué was given on April 1 announcing that Ivo Andrić had been appointed minister plenipotentiary and envoy extraordinary to Berlin. Andrić arrived in Berlin on April 12, and on April 19 presented his credentials to the chancellor of the Reich – Adolph Hitler. In the fall, after the Germans had occupied Poland and sent many scholars and writers to concentration camps, Andrić interceded before the German authorities to save many of them from imprisonment. Politicians in Belgrade, however, did not always count on their envoy, and many contacts were maintained with German authorities that bypassed Andrić. In spite of such circumstance, the writer published: the short story “Čaša” (Glass) and the texts “Staze” (Paths) and “Vino” (Wine) in the Serbian Literary Gazette during 1940. In early spring 1941, Andrić submitted his resignation to the authorities in Belgrade: “…Today I am obliged, above all by many official and personal reasons, to request that I be relieved of these duties and recalled from my current post as soon as possible…” His request was not granted and on March 25 he was present at the signing of the Tripartite Pact in Vienna as the official representative of Yugoslavia. The day after Belgrade was bombed by Germany, April 7, Andrić left Berlin with the other Legation staff. After rejecting the German authorities’ offer to go to the safety of Switzerland, but without the other members of the legation and their families, he chose to return to occupied Belgrade. In November he retired from the diplomatic service but refused to receive a pension. He lived a reclusive life on Prizrenska Street, renting a room from lawyer Brana Milenković. He refused to sign the Appeal to the Serbian people that condemned resistance to the occupying forces. He also refused to let the Serbian Literary Association publish his short stories while “the people are suffering and dying”. In the quiet of his rented room he first wrote Travnička hronika (The Bosnian Story), and then at the end of 1944 completed Na Drini ćuprija (Bridge on the Drina). Both novels were to be published in Belgrade several months after the end of the war, and his novel Gospođica (The Woman from Sarajevo) was published at the end of 1945 in Sarajevo.

During the first postwar years Ivo Andrić became the president of the Yugoslav Writers Association, vice president of the Society for Cultural Cooperation with the Soviet Union, and  counselor of the third meeting of ZAVNOBIH (Antifascist Liberation Council of Bosnia and Herzegovina). In 1946 he lived in both Belgrade and Sarajevo and became a full member of the Serbian Academy of Science and Art. That year he published, among other things, the short stories “Zlostavljanje” (Mistreatment) and “Pismo iz 1920” (Letter from 1920). The next year he became a member of the Presidium of the People’s Assembly of NR Bosnia and Herzegovina and published “Priča o vezirovom slonu” (The Story of the Vizier’s Elephant), several texts about Vuk Karadžić and Njegoš, and during 1948 his “Priča o kmetu Simanu” (Story of Siman the Serf) was printed for the first time. During the next few years he was quite involved in public affairs: he gave lectures, spoke at public meetings, and traveled as a member of different delegations to the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Poland, France and China. He published primarily shorter texts, excerpts from short stories, and the stories “Bife Titanik” (The Titanic Bar) (1950), “Znakovi” (Signs) (1951), “Na sunčanoj strani” (On the Sunny Side), “Na obali” (On the Shore), “Pod grabićem” (Under the Woods), “Zeko” (1952), and “Aska i vuk” (Aska and the Wolf), “Nemirna godina” (Restless year) and “Lica” (Faces) (1953). In 1954 he became a member of the Yugoslav Communist Party. He was the first to sign the Novi Sad Agreement on the Serbo-Croatian language. That year Matica Srpska published Prokleta avlija (The Damned Yard) and the short story “Igra” (Dance) appeared in 1956.

counselor of the third meeting of ZAVNOBIH (Antifascist Liberation Council of Bosnia and Herzegovina). In 1946 he lived in both Belgrade and Sarajevo and became a full member of the Serbian Academy of Science and Art. That year he published, among other things, the short stories “Zlostavljanje” (Mistreatment) and “Pismo iz 1920” (Letter from 1920). The next year he became a member of the Presidium of the People’s Assembly of NR Bosnia and Herzegovina and published “Priča o vezirovom slonu” (The Story of the Vizier’s Elephant), several texts about Vuk Karadžić and Njegoš, and during 1948 his “Priča o kmetu Simanu” (Story of Siman the Serf) was printed for the first time. During the next few years he was quite involved in public affairs: he gave lectures, spoke at public meetings, and traveled as a member of different delegations to the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Poland, France and China. He published primarily shorter texts, excerpts from short stories, and the stories “Bife Titanik” (The Titanic Bar) (1950), “Znakovi” (Signs) (1951), “Na sunčanoj strani” (On the Sunny Side), “Na obali” (On the Shore), “Pod grabićem” (Under the Woods), “Zeko” (1952), and “Aska i vuk” (Aska and the Wolf), “Nemirna godina” (Restless year) and “Lica” (Faces) (1953). In 1954 he became a member of the Yugoslav Communist Party. He was the first to sign the Novi Sad Agreement on the Serbo-Croatian language. That year Matica Srpska published Prokleta avlija (The Damned Yard) and the short story “Igra” (Dance) appeared in 1956.

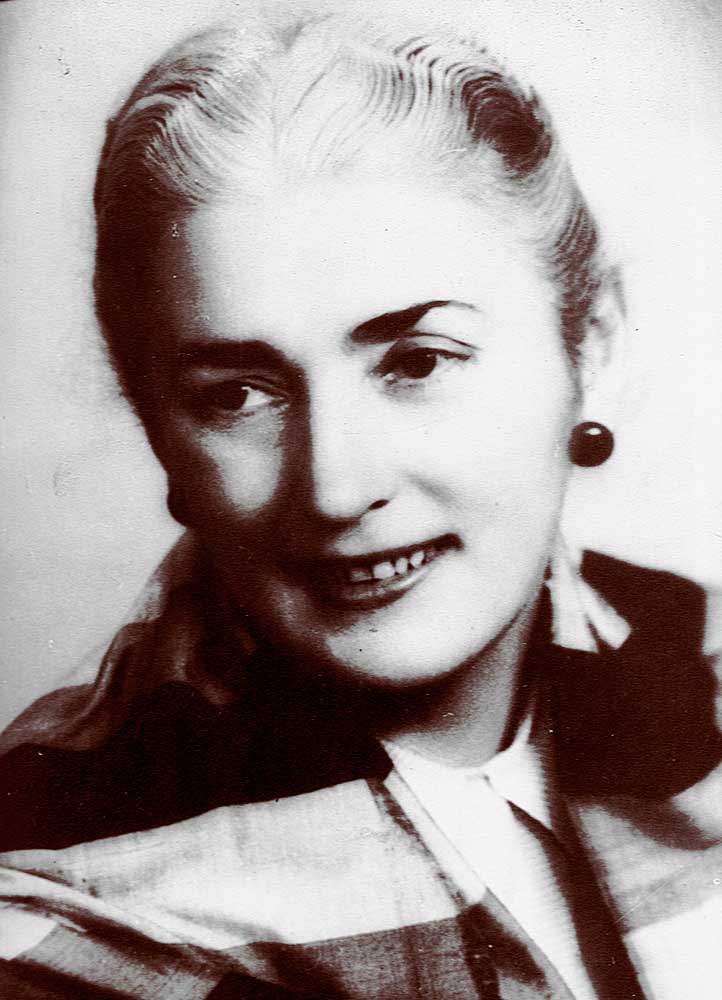

Milica Babi}In 1958 at the age of sixty-six, Ivo Andrić married his sweetheart of many years, Milica Babić, a costume designer at the National Theater in Belgrade and the widow of Nenad Jovanović. He moved into his first apartment with his wife – Proleterskih Brigada Street 2a. That year he published the short stories “Panorama”, “U zavadi sa svetom” (Fighting with the World) and the only preface that he ever wrote for a book: the introduction to the book “Nekrolog jednoj čaršiji” (Necrology of a Downtown) by Zuko Džumhur.

Milica Babi}In 1958 at the age of sixty-six, Ivo Andrić married his sweetheart of many years, Milica Babić, a costume designer at the National Theater in Belgrade and the widow of Nenad Jovanović. He moved into his first apartment with his wife – Proleterskih Brigada Street 2a. That year he published the short stories “Panorama”, “U zavadi sa svetom” (Fighting with the World) and the only preface that he ever wrote for a book: the introduction to the book “Nekrolog jednoj čaršiji” (Necrology of a Downtown) by Zuko Džumhur.

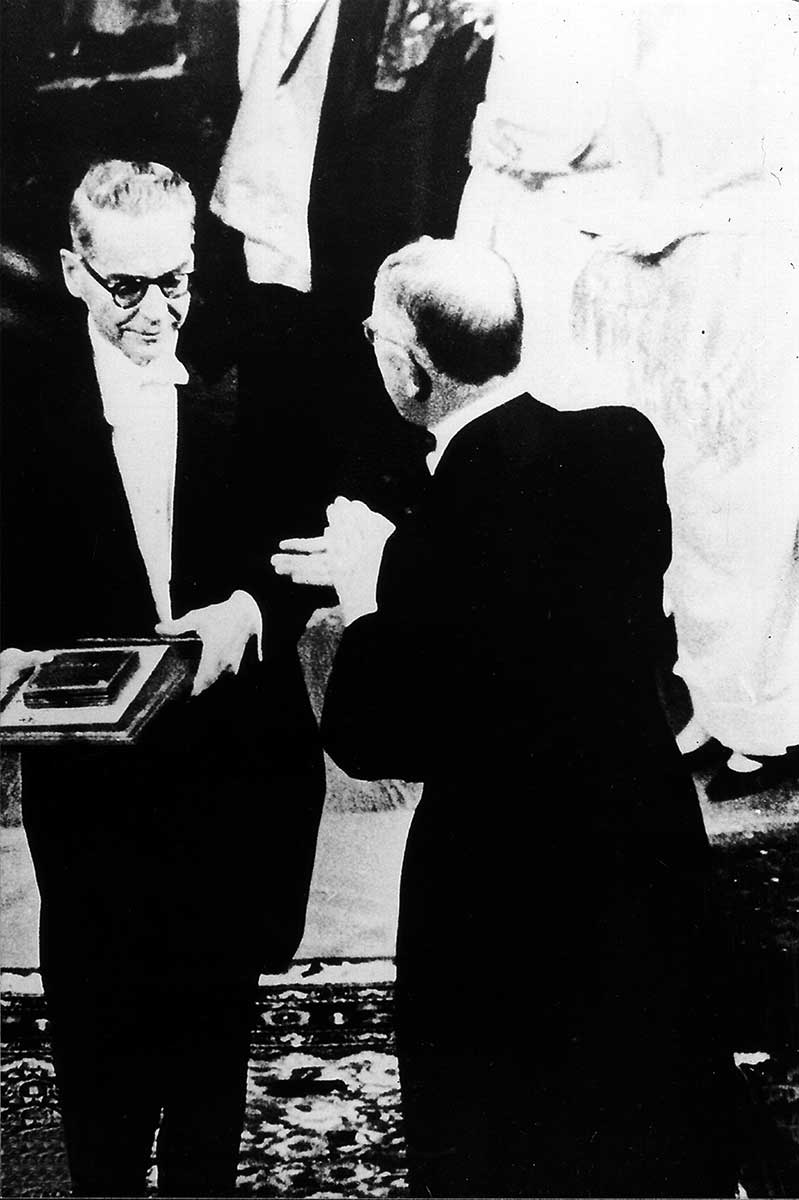

“For the epic strength” with which he “shaped the motifs and fates from the history of his country”, Ivo Andrić received theNobel Prize Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961. He expressed his gratitude for this recognition on December 10, 1961 in his speech “On Stories and Storytelling” in which he expounded upon his basic principles of writing. Although a considerable number of his works had already been translated into many languages, after he received the Nobel Prize there was enormous interest in the world for the works of this writer from the Balkans, and his novels and short stories were printed in more than thirty languages. In spite of the fact that he turned down many invitations, Andrić went to Sweden, Switzerland, Greece and Egypt those years. He donated his entire Nobel Prize money to the library fund in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in two parts. In addition, he frequently participated in activities to assist libraries and donated money to charity. In 1963, the Publishers’ Association (consisting of the publishing houses Prosveta, Mladost, Svjetlost and Državna založba Slovenije) published the first Collected Works of Ivo Andrić in ten volumes. The next year he went to Poland where he was awarded an honorary doctorate at the University of Jagiellonian in Krakow. He wrote very little, but his books were continuously reprinted, both locally and abroad. In March 1968 Andrić’s wife Milica died in their family house in Herceg Novi.

Literature in 1961. He expressed his gratitude for this recognition on December 10, 1961 in his speech “On Stories and Storytelling” in which he expounded upon his basic principles of writing. Although a considerable number of his works had already been translated into many languages, after he received the Nobel Prize there was enormous interest in the world for the works of this writer from the Balkans, and his novels and short stories were printed in more than thirty languages. In spite of the fact that he turned down many invitations, Andrić went to Sweden, Switzerland, Greece and Egypt those years. He donated his entire Nobel Prize money to the library fund in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in two parts. In addition, he frequently participated in activities to assist libraries and donated money to charity. In 1963, the Publishers’ Association (consisting of the publishing houses Prosveta, Mladost, Svjetlost and Državna založba Slovenije) published the first Collected Works of Ivo Andrić in ten volumes. The next year he went to Poland where he was awarded an honorary doctorate at the University of Jagiellonian in Krakow. He wrote very little, but his books were continuously reprinted, both locally and abroad. In March 1968 Andrić’s wife Milica died in their family house in Herceg Novi.

The following years Andrić endeavored to reduce his social activities to a minimum. He read a lot and wrote very little. His health slowly deteriorated and he often spent time in hospitals and spas undergoing treatment. On March 13, 1975, one of the greatest creators in the Serbian language left this world, a writer of mythmaking powers and the wise chronicler of the Balkan cauldron.

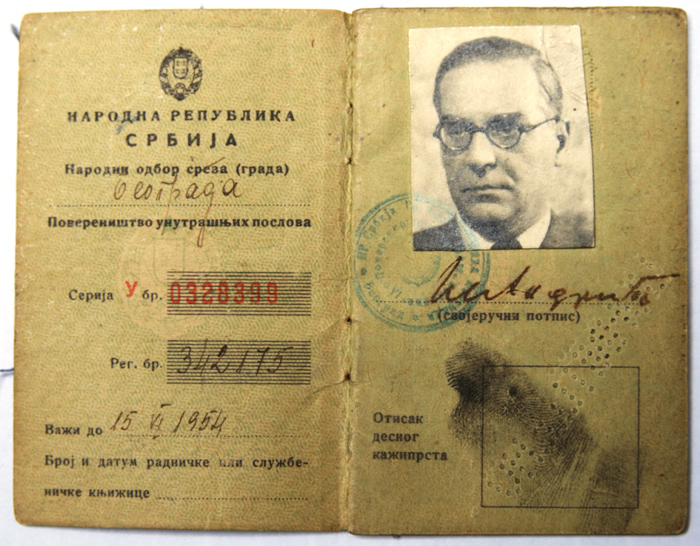

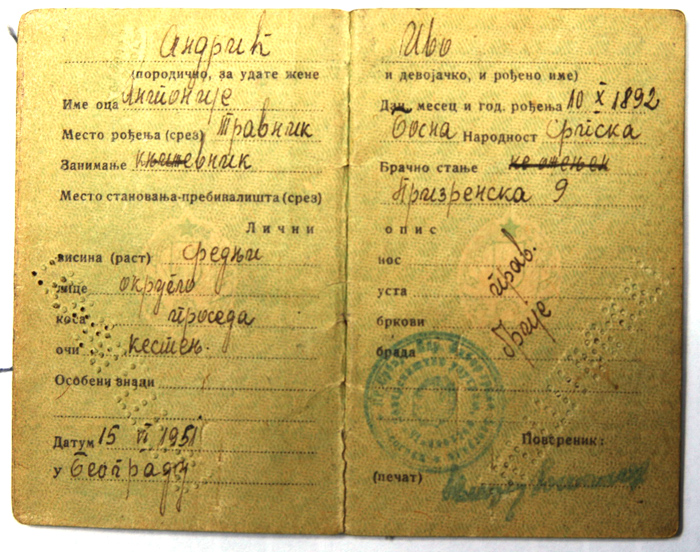

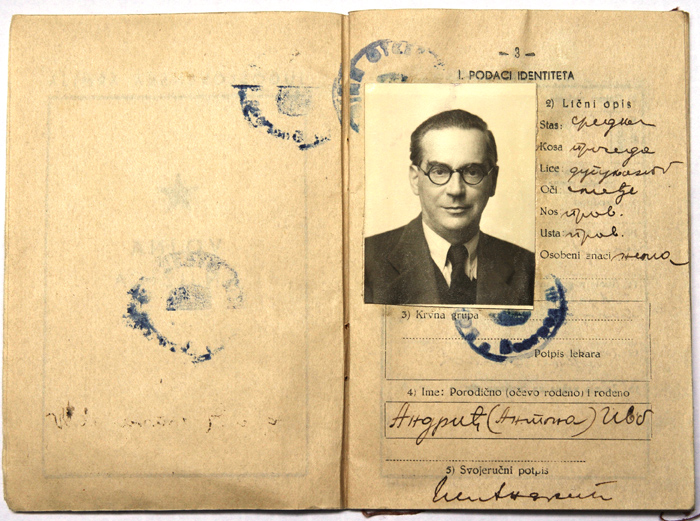

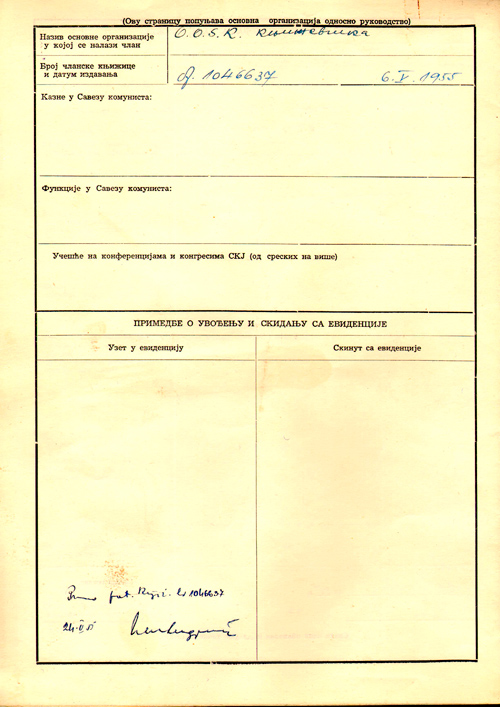

Some of the Andrić's personal documents.

Lična karta Ive Andrića, 1951.

Vojna knjižica Ive Andrića, 1952.

Evidentni list za prijem u KPJ, 1955.