Review

The novel is written quickly, between July 1942 and December 1943. An outline of some fifty pages has been preserved, as well as jotting treating various aspects of the subject matter. For instance, “The Bridge on the Žepa” forms part of this preliminary process.

The novel is written quickly, between July 1942 and December 1943. An outline of some fifty pages has been preserved, as well as jotting treating various aspects of the subject matter. For instance, “The Bridge on the Žepa” forms part of this preliminary process.

“The Bridge on the Drina” is the cronicle of a small town, and in particular of the focal point of that town: the bridge over the river Drina. The town is Višegrad on the eastern edge of Bosnia, near the border of Serbia. The chronicle traces its history from the sixteenth century to the First World War, and uses the bridge to bind the individual chapters and stories together. The emphasis is on the evolution of a common mentality in the town, deriving from common experience and a common heritage of legend and anecdote. The population of the town is mixed, but Andrić chooses in this case to stress the coherence of the whole. This is achieved partly by the time-scale, but also by Andrić's basic intention in the work. This is to contrast the transience and insignificance of individual human life with the broader perspective of life as itself enduring, a constant ebThe first page of the novel The Bridge on the Drinab and flow. On this level the bridge provides not only a structural but also a symbolic link.

Each chapter or anecdote is in some way connected with the bridge. It is the focal point of the town, and most important events occur on or near it.  Such an apparently simple structural function contributes also to the main direction of the work, which depicts the growth, from a series of disparate events, of a common heritage.

Such an apparently simple structural function contributes also to the main direction of the work, which depicts the growth, from a series of disparate events, of a common heritage.

The movement of the cronicle through the four centuries it describes is not steady. The first event of major importance to the people of Višegrad, the building of the bridge in the mid-sixteenth century, is described in detail over three chapters; the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when no important historical events affected the town, pass by in a single chapter; the nineteenth century covers ten chapters, and the years from 1900 to 1914, the remainder of the work, further nine chapters. Such a scheme allows the author to describe the main events affecting the life of the town in detail and also suggest an awareness of history as never uniformly well-konown or related. The static nature of the centuries of Ottoman rule is then highlighted by the changes which take place during the nineteenth century and increase in speed and scope with Austrian annexation of Bosnia and Hercegovina at the end of that century. The clearest implication of the broad time-scale is the predictable one in Andrić’s work: that, for all these events and changes, nothing of significance alters.

The movement of the cronicle through the four centuries it describes is not steady. The first event of major importance to the people of Višegrad, the building of the bridge in the mid-sixteenth century, is described in detail over three chapters; the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when no important historical events affected the town, pass by in a single chapter; the nineteenth century covers ten chapters, and the years from 1900 to 1914, the remainder of the work, further nine chapters. Such a scheme allows the author to describe the main events affecting the life of the town in detail and also suggest an awareness of history as never uniformly well-konown or related. The static nature of the centuries of Ottoman rule is then highlighted by the changes which take place during the nineteenth century and increase in speed and scope with Austrian annexation of Bosnia and Hercegovina at the end of that century. The clearest implication of the broad time-scale is the predictable one in Andrić’s work: that, for all these events and changes, nothing of significance alters.

“The Bridge on the Drina” can be seen as a portrait of history itself. History is made as much by individual personalities as by mass movements and the upheavals created by the rise and fall of empires.

Fragment

I Chapter

For the greater part of its course the river Drina flows through narrow gorges between steep mountains or through deep ravines with precipitous banks. In a few places only the river banks spread out to form valleys with level or rolling stretches of fertile land suitable for cultivation and settlement on both sides. Such a place exists here at Višegrad, where the Drina breaks out in a sudden curve from the deep and narrow ravine formed by the Drina makes here is is particularly sharp and the mountains on both sides are so steep and so close together that they look like a solid mass out of which the river flows directly as from a dark wall. Then the mountains suddenly widen into an irregular amphitheatre whose widest extent is not more than about ten miles as the crow flies.

Here, where the Drina flows with the whole force of its green and foaming waters from the apparently closed mass of the dark steep mountains, stands a great clean-cut stone bridge with eleven wide sweeping arches. From this bridge spreads fanlike the whole rolling valley with the little oriental town of Višegrad and all its surroundings, with hamlets nestling in the folds of the hills, covered with meadows, pastures and plum-orchards, and criss-crossed with walls and fences and dotted with shaws and occasional clumps of evergreenes. Looked at from a distance through the broad arches of the white bridge it seems as if one can see not only the green Drina, but all that fertile and cultivated countryside and the southern sky above.

On the right bank of the river, starting from the bridge itself, lay and partly on the hillside. On the other side of teh bridge itself, along the left bank, stretched the Maluhino Polje, with a few scattered haouses along the road wich led to Sarajevo. Thus the bridge, uniting the two parts of the Sarajevo road, linked the town with its surrounding villages.

Actually, to say 'linked' was just as true as to say that the sun rises in the morning so that men may see around them and finish their dayly tasks, and sets in the veningthat they may be able to sleep and rest from the labours of the day. For this great stone bridge, a rare structure of unique beauty, such as many richer and busier towns do not possess (There are only two others such as this in the whole Empire, they used to say in old times) was the one real and permanent crossing in the whole middle und upper course of the Drina and an indispensanble link on the road between Bosnia and Serbia and further, beyond Serbia, with other parts of the Turkish Empire, all the way to Stambul. The town and its outskirts were only the settlements wcich always and inevitably grow up around an important centre of communications and on either side of great and important bridges.

Here also in time the houses crowded together and the settlemnts multiplied at both ends of the bridge. The town owned its existence to the bridge and grew out of it as if from an imperishable root.

In order to see a picture of the town and understand it and its relation to the bridge clearly, it must be said that there was another bridge in the town and another river. This was the river Rzav, with a wooden bridge across it. At the very end of the town the Rzav flows into the Drina, so that the centr and at the same time the main part of the town lay on a sandy tongue of land between two rivers, the great and the samll, which met there and its scattered outskirts streched out from the both sides of the bridges, along the left bank of the Drina and the right bank of the Rzav. It was a town on the water. But even though another river existed and another bridge, the words 'on the bridge' never meant on the Rzav bridge., a simple wooden structure without beaty and without history, that had no reason for its existence save to serve the townspeople and their animals as a crossing, but only uniqeuly the stone bridge over the Drina.

The bridge was about two hundred and fifty paces long and about ten paces wide save in the middle where it widened out into two compeletely equal terraces placed symmetrically on either side of the roadway and making it twice its normal width. This was the part of the bridge known as the kapia. Two buttresses had been built on each side of the central pier which had been splayed out towards the top, so that to right and left of the roadway there were two terraces daringly and harmoniously projecting outwards from the straight line of the bridge over the noisy green waters far below. The two terraces were about five paces long and the same in width and were bordered, as was the whole length of the bridge, by a stone parapet. Otherwise, they were open and uncovered. That on the right as one came from the town was called the sofa. It was raised by two steps and bordered by benches for which the parapet served as a back steps, benches and parapet were all made of the same shining stone. That on the left, opposite the sofa, was similar but without benches. In the middle of the parapet, the stone rose higher than a man and in it, near the top, was inserted a plaque of white marble with a rich Turkish inscription, a tarih, with a carved chronogram which told in thirthen verses the name of the man who built the bridge and the year in which it was built. Near the foot of this stone was a fountain, a thin stream of water flowing from the mouth of a stone snake. On this part of the terrace a coffee-maker had installed himself with his copper vessels and Turkish cups and ever-lighted charcoal brazier, and an apprentice who took the coffee over the way to the guests on the sofa. Such was the kapia.

On teh bridge and its kapia, about it or in connection with it, flowed and developed, as we shall see, the life of the townsmen. In all tales about personal, family or public events the words 'on the bridge' could always be heard. Indeed on the bridge over the Drina were the first steps of childhood and the first games of boyhood.

The Christian children, born on the left bank of the Drina, crossed the bridge at once in the first days of their lives, for they were always taken across in their first week to be christened. But all the other children, those who were born on the right bank and the Moslem children who who were not christened at all, passed, as had once their fathers and their grandfathers, the main part of their childhood on or around the bridge. They fished around it or hunted doves under its arches. From their very earliest years, their eyes grew accustomed to the lovely lines of this great stone structure built of shining porous stone, regularly and faultlessy cut. They knew all the bosses and concavities of the masons, as well as all the tales and legends associated with the existence and building of the bridge, in which reality and imagination, waking and dream, were wondrefully and inextricably mingled. They had always known these things as if they had come into the world with them, even as they knew their prayers, but could not remember from whom they had learnt them nor when they had first heard them.

They knew that the bridge had been built by the Grand Vezir, Mehmaed Pasha, who had been born in the nearby village of Sokolovići, just on the far side of one of those mountains which encircled the bridge and the town. Only a Vezir could have given all that was needed to build this lasting wonder of stone (a Vezir – to the children’s minds that was something fabulous, immense, terrible and far from clear). It was built by Rade the Mason, who must have lived for hundreds of years to have been able to build all that was lovely and lasting in Serbian lands, that legendary and in fact nameless master whom all people desire and dream of, since they do not want to have remember or be indebted to too many, even in memory. They knew that the vila of the boatmen had hindered its building, as always and everywhere there is someone to hinder building, destroying by night what had been built by day, until ‘something’ had whispered from the waters and counselled Rade the Mason to find two infant children, twins, brother and sister, named Stoja and Ostoja, and wall them into central pier of the bridge. A reward was promised to whoever found them and brought them hither.

At last the guards found such twins, still at the breast, in a distant village and the Vezir’s men took them away by force; but when they were taking them away, their mother would not be parted from them and, weeping and wailing insensible to blows and to curses, stumbled after them as far as Višegrad itself, where she succeeded in forcing her way to Rade the Mason.

The children were walled into the pier, for it could not be otherwise, but Rade, they say, had pity on them and left openings in the pier through which the unhappy mother could feed her sacrificed children. Those are the finely carved blind windows, narrow as loopholes, in which the wild doves now nest. In memory of that, the mother’s milk has flowed from those walls for hundreds of years. That is the thin white stream which, at certain times of year, flows from that faultless masonry and leaves an indelible mark of the stone. (The idea of woman’s milk stirs in the childish mind a feeling at once too intimate and too close, yet at the same time vague and mysterious like Vezirs and masons, which disturbs and repulses them.) Men scrape those milky traces off the piers and sell them as medical powder to women who have no milk after giving birth.

In the central pier of the bridge, below the kapia, there is a larger opening, a long narrow gateway without gates, like a gigantic loophole. In that pier, they say, is a great room, a gloomy hall, in which a black Arab lives. All the children know this. In their dreams and in their fancies he plays a great role. If he should appear to anyone, that man must die. But Hamid, the asthmatic porter, with bloodshot eyes, continually drunk or suffering from a hangover, saw him one night and that very same night he died, over there by the wall. It is true that he was blind drunk at the time and passed the night on the bridge under the open sky in a temperature of –15 °C. The children used to gaze from the bank into the dark opening as into a gulf which is both terrible and fascinating. They would agree to look at it without blinking and whoever first saw anything should cry out. Open-mouthed they would peer into that deep dark hole, quivering with curiosity and fear, until it seemed to some anemic child that the opening began to sway and to move like a black curtain, or until one of them, mocking and inconsiderate (there is always at least one such), shouted ‘The Arab” and pretended to run away. That spoilt the game and aroused disillusion and indignation amongst those who loved the play of imagination, hated irony and believed that by looking intently they could actually see and feel something. At night, in their sleep, many of them would toss and fight with the Arab from the bridge as with fate until their mother woke them and so freed them from this nightmare. Then she would give them cold water to drink ‘to chase away the fear’ and make them say the name of God, and the child, overtaxed with daytime childish games, would fall asleep again into the deep sleep of childhood where terrors can no longer take shape or last for long.

Up river from the bridge, in the steep banks of gray chalk, on both sides of the river, can be seen rounded hollows, always in pairs at regular intervals, as if cut in the stone were the hoof prints of some horse of supernatural size; they led downwards from the Old Fortress, descended the scarp towards the river and then appeared again on the farther bank, where they were lost in the dark earth and undergrowth.

The children who fished for tiddlers all day in the summer along these stony banks knew that these were hoofprints of ancient days and long dead warriors. Great heroes lived on earth in those days, when the stone had not yet hardened and was soft as the earth and the horses, like the warriors, were of colossal growth. Only for the Serbian children these were the prints of the hooves of Šarac, the horse of Kraljević Marko, which had remained there from the time when Kraljević Marko himself was in prison up there in the Old Fortress and escaped, flying down the slope and leaping the Drina, for at that time there was no bridge. But the Turkish knew that it had not been Kraljević Marko, nor could it have been (for whence could a bastard Christian dog have had such strength or a horse!) any but Djerzelez Alija on his winged charger which, as everyone knew, despised ferries and ferrymen and leapt over rivers as if they were watercourses. They did not even squabble about this, so convinced were both sides in their own belief. And there was never an instance of any one of them being able to convince another, or that any one had changed his belief.

In these depressions which were round and as wide and deep as rather large soup-bowls, water still remained long after rain, as though in stone vessels. The children called these pits, filled withtepid rainwater, wells and, without distinction of faith, kept the tiddlers there which they caught on their lines.

On the left bank, standing alone, immediately above the road, there was a fairly great earthen barrow, formed of some kind of hard earth grey and almost like stone. On it nothing grew or blossomed save some short grass, hard and prickly as barbed wire. That tumulus was the end and frontier of all the children's gamnes around the bridge. That wasc the spot which at one time was called Radisav's tomb. They used to tell that he was some sort of Serbian hero, a man of power. When the Vezir, Mehmed Pasha, had first thought of building the bridge on the Drina and sent his men here, everyone submitted and was summoned to forced labour. Only this man, radisav, stirred up the people to revolt and told the Vezir not to continue with this work for he would meet with great difficulties in building a bridge across the Drina. And the Vezir had many troubles before he succeeded in overcoming Radisav for he was a man greater then other men; there was no rifle or sword that could harm him, nor was there rope or chain that could bind him. He broke all of them like thread, so great was the power of the talisman that he had with him. And who knows what might have happened and whether the Vezir would ever have been able to build the bridge, had he not found some of his men who were wise and skilful, who bribed and questioned Radisav's servant. Then they took Radisav by surprise and drowned him while he was asleep, binding him with silken ropes for against silk his talisman could not help him. The Serbian women believe that there is one night of the year when a strong white light can be seen falling on that tumulus direct from heaven; and that takes place sometime in autumn between belief and unbelief, remained on vigil by the windows overlooking Radisav's tomb have never managed to see this heavenly fire, for they were all overcome by sleep before midnight came. But there had been travellers, who knew nothing of this, who had seen a white light falling on the tumulus above the bridge as they returned to the town by night.

The Turks in the town, on the other hand, have long told that on that spot a certain dervish, by name Sheik Turhanija, died as a martyr to the faith. He was a great hero and defended on this spot the crossing of the Drina against an infidel army. And that on this spot there is neither memorial nor tomb, for such was the wish of the dervish himslef , for he wanted to be buried without mark or sign, so that no one should know who was there. For, if ever again some infidel army should invade by this route, then he would arise from under his tumulus and hold them in check, as he had once done, so they should be able to advance no farther than the bridge at Viđegrad. And therefore heaven now and again shed its light upon his tomb.

Thus the life of the children of the town was played out under and about the bridge in innocent games and childish fancies. With the first years of maturity, when life’s cares and struggles and duties had already begun, this life was transffered to the bridge itself, right to the kapia, where youthful imagination found other food and new fields.

At and around the kapia were the first stirrings of love, the first passing glances, flirtations and whisperings. There too were the first deals and bargains, quarrels and reconciliations, meetings and waitings. There, on the stone parapet of the bridge, were laid out for sale the first cherries and melons, the early morning salep and hot rolls. There too gathered the beggars, the maimed and the lepers, as well as the young and healthy who wanted to see and be seen, and all those who had something remarkable to show in produce, clothes or weapons. There too the elders of the town often sat to discuss public matters and common troubles, but even more often young men who only knew how to sing and joke. There, on great occasions or times of change, were posted proclamations and public notices (on the raised wall below the marble plaque with the Turkish inscription and above the fountain), but there too, right up to 1878, hung or were exposed on stakes the heads of all those who for whatever reason had been executed in that frontier town, especially in years of unrest, were frequent and in some years, as we shall see, almost of daily occurrence.

Weddings or funerals could not cross the bridge without stopping at the kapia. There the wedding guests would usually preen themselves and get into their ranks before entering the market-place. If the times were peaceful and carefree they would hand the plum-brendy around, sing, dance the kolo and often delay there far longer than they had intended. And for funerals, those who carried the bier would put it down to rest for a little there on the kapia where the dead man had in any case passed a good part of his life.

The kapia was the most important part of the bridge, even as the bridge was the most important part of the town, or as a Turkish traveler, to whom the people of Višegrad had been very hospitable, wrote in his account of his travels: ‘their kapia is the heart of the bridge, which is the heart of the town, which must remain in everyone’s heart’. It showed that the old masons, who according to the old tales had struggled with vilas and every sort of wonder and had been compelled to wall up living children, had a feeling not only for permanence and beauty of their work but also for the benefit and convenience which the most distant generations were to derive from it. When one knows well everyday life here in the town and thinks it over carefully, then one must say to oneself that there are really only a very small number of people in this Bosnia of ours who have so much pleasure and enjoyment as does each and every townsman on the kapia.

Naturally winter should not be taken into account, for then only whoever was forced to do so would cross the bridge, and then he would lengthen his pace and bend his head before the chill wind that blew uninterruptedly over the river. Then, it was understood, there was no loitering on the open terraces of the kapia. But at every other time of the year the kapia was a real boon for great and small. Then every citizen could, at any time of day or night, go out to the kapia and sit on the sofa, or hang about it on business or in conversation. Suspended some fifteen metres above the green boisterous waters, this stone sofa, floated in space over the water, with dark green hills on three sides, the heavens, filled with clouds and stars, above and the open view down river like a narrow amphitheatre bounded by the dark green hills on three sides, the heavens, filled with clouds or stars, above and the open view down river like a narrow amphitheatre bounded by the dark blue mountains behind.

How many Vezirs or rich men are there in the world who could indulge their joy or their cares, their moods or their delights in such a spot? Few, very few. But how many of our townsmen have, in the course of centuries and the passage of generations, sat here in the dawn or twilight or evening hours and unconsciously measured the whole starry vault above! Many and many of us have sat there, eternally the same yet eternally tangled in some new manner. Someone affirmed long ago (it is true that he was a foreigner and spoke in jest) that this kapia had had an influence on the fate of the town and even on the character of its citizens. In those endless sessions, the stranger, the stranger said, one must search for the key to the inclination of many of our townsmen to reflection and dreaming and one of the main reasons for that melancholic serenity for which the inhabitants of the town are renewed.

In any case, it cannot be denied that the people of Višegrad have from olden times been considered, in comparison with the people of other towns, as easy-going men, prone to pleasure and free with their money. Their town is well placed, the villages around it are rich and fertile, and money, it is true, passes in abundance through Višegrad, but it does not stay there long. If one finds there some thrifty and economical citizen without any sort of vices, then he is certainly some newcomer; but the waters and the air of Višegrad are such that his children grow up with open hands and widespread fingers and fall victims to the general contagion of the spendthrift and carefree life of the town with its motto: ‘Another day another gain.’

They tell the tale that Starina Novak, when he felt his strength failing and was compelled to give up his role a highwayman in the Romania Mountains, thus taught the young man Grujić who was to succeed him:

When you are sitting in ambush look well at the traveler who comes. If you see that he rides proudly and that he wears a red corselet and silver bosses and white gaiters, then he is from Foča. Strike at once, for he has wealth both on him and in his saddlebags. If you see a poorly dressed traveler, with bowed head, hunched on his horse as if we were going out to beg, then strike freely, for he is a man from Rogatica. They are all alike, misers and tight-fisted but as full of money as a pomegranate. But if you see some mad fellow, with legs crossed over the saddlebow, beating on a drum and singing at the top of his voice, don’t strike and do not soil your hands for nothing. Let the rascal go his way. He is from Višegrad and he has nothing, for money does not stick to such men.’

All this goes to confirm the opinion of that foreigner. But none the less it would be hard to say with certainty that this opinion is correct. As in so many other things, here too it is easy to determine what is cause and what effect. Has the kapia made them what they are, or on the contrary was it imagined in their souls and understandings and built for them according to their needs and customs? It is a vain and superfluous question. There are no buildings that have been built by chance, remote from the human society where they have grown and its needs, hopes and understandings, even as there are no arbitrary lines and motiveless forms in the work of the masons. The life and existence of every great, beautiful and useful building, as well as its relation to the place where it has been built, often bears within itself complex and mysterious drama and history. However, one thing is clear; that between the life of the townsmen and that bridge, there existed a centuries-old bond. Their fates were so intertwined that they could not be imagined separately and could not be told separately. Therefore the story of the foundation and destiny of the bridge is at the same time the story of the life of the town and of its people, from generation to generation, even as through all the tales about the town stretches the line of the stone bridge with its eleven arches and the kapia in the middle, like a crown.

XXIV (the last) Chapter

(...)

So be it, thought the hodja. If they destroy here, then somewhere else someone else is building. Surely there are still peaceful countries and men of good sense who know of God’s love? If God had abandoned this unlucky town on the Drina, he had surely not abandoned the whole world that was beneath the skies? They would not do this forever. But who knows? (Oh, if only he could breath a little more deeply, get a little more air!) Who knows? Perhaps this impure infidel faith that puts everything in order, cleans everything up, repairs and embellishes everything only in order suddenly and violently to demolish and destroy, might spread through the whole world; it might make of all God’s world an empty field for its senseless building and criminal destruction, a pasturage for its insatiable hunger and incomprehensible demands? Anything might happen. But one thing could not happen: it could not be that great and wise men of exalted soul who would raise lasting buildings for the love of God, so that the world should be more beautiful and man live in it better and more easily, should everywhere and for all time vanish from this earth. Should they too vanish, it would mean that the love of God was extinguished and had disappeared from the world. That could not be.

Filled with his thoughts, the hodja walked more heavily and slowly.

Now they could clearly be heard singing in the market-place. If only he had been able to breath in more air, if only the road were less steep, if only he were able to reach home, lie down on his divan and see and hear someone of his own about him! That was all that he wanted now. But he could not. He could no longer maintain that fine balance between his breathing and his heartbeats; his heart had now completely stifled his breath, as had sometimes happened to him in dreams. Only from this dream there was no awakening to bring relief. He opened his mouth wide and felt his eyes bulging in his head. The slope which until then had been growing steeper and steeper was now quite close to his face. His whole field of vision was filled by that dry, rough road which became darkness and enveloped him.

On the slope which led upwards to Mejdan lay Alihodja and breathed out his life in short gasps.

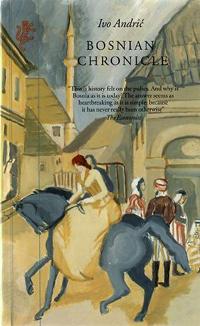

A timeless saga of intrigue and conquest in the heart of Bosnia presents the struggle for supremacy in a region that stubbornly refuses to submit to any outsider. Andric's sweeping novel spans the seven years 1807-1814, when French and Austrian consul served alongside the Turkish Viziers in the remote Bosnian town of Travnik, distant outpost of the Ottoman Empire. Divided as the community is, Muslims, Catholic and Orthodox Christians, Jews and Gypsies all unite in a common contempt for their visitors. Isolated in a claustrophobic atmosphere of suspicion and mutual distrust, the consuls and Viziers vie with each other, following the fluctuations of their respective foreign policies. When international politics permit however, they console each other as best they can in this harsh and hostile land.

A timeless saga of intrigue and conquest in the heart of Bosnia presents the struggle for supremacy in a region that stubbornly refuses to submit to any outsider. Andric's sweeping novel spans the seven years 1807-1814, when French and Austrian consul served alongside the Turkish Viziers in the remote Bosnian town of Travnik, distant outpost of the Ottoman Empire. Divided as the community is, Muslims, Catholic and Orthodox Christians, Jews and Gypsies all unite in a common contempt for their visitors. Isolated in a claustrophobic atmosphere of suspicion and mutual distrust, the consuls and Viziers vie with each other, following the fluctuations of their respective foreign policies. When international politics permit however, they console each other as best they can in this harsh and hostile land. loyalties, the story is inevitably eerily relevant to readers today. Ottoman viziers, French consuls, and Austrian plenipotentiaries are consumed by a ceaseless game of diplomacy and double-dealing: expansive and courtly face-to-face, brooding and scheming behind closed doors. As they have for centuries, the Bosnians themselves observe and endure the machinations of greater powers that vie, futilely, to absorb them. Ivo Andric posses the rare gift in a historical novelist of creating a period-piece, full of local colour, and at the same time characters who might have been living today. His masterwork is imbued with the richness and complexity of a region that has brought much tragedy to our century and known so little peace.

loyalties, the story is inevitably eerily relevant to readers today. Ottoman viziers, French consuls, and Austrian plenipotentiaries are consumed by a ceaseless game of diplomacy and double-dealing: expansive and courtly face-to-face, brooding and scheming behind closed doors. As they have for centuries, the Bosnians themselves observe and endure the machinations of greater powers that vie, futilely, to absorb them. Ivo Andric posses the rare gift in a historical novelist of creating a period-piece, full of local colour, and at the same time characters who might have been living today. His masterwork is imbued with the richness and complexity of a region that has brought much tragedy to our century and known so little peace. This novel by Andrić was originally published in Serbian in 1945 and is one of the treee novels that make up the "Bosnian Trilogy". The other two are "Bosnian Chronicle" and "The Bridge on the Drina".

This novel by Andrić was originally published in Serbian in 1945 and is one of the treee novels that make up the "Bosnian Trilogy". The other two are "Bosnian Chronicle" and "The Bridge on the Drina".

The novel is carefully thought out and fully imagined, with solid passages of description in the nineteenth-century manner and scrupulous attentions to the job of relating the individual life to the broader pattern of social and economical change With brilliant economy Andrić sketches the stages through which Miss Raika hoards and increases her inheritance: Sarajevo in the era of provincial usury, the economic upheavals and disintegration of the First World War, staid Belgrade headily embarking on the jazz age when the war is over, the pinched depression years during which Miss Raika dies. The requisite drama – the testing of the ruling passion – is present in the form of a young man whose physical resemblance to a beloved uncle long dead touches Miss Raika’s heart enough to make her swerve, though only momentarily, from her objective of never parting with her money.

The novel is carefully thought out and fully imagined, with solid passages of description in the nineteenth-century manner and scrupulous attentions to the job of relating the individual life to the broader pattern of social and economical change With brilliant economy Andrić sketches the stages through which Miss Raika hoards and increases her inheritance: Sarajevo in the era of provincial usury, the economic upheavals and disintegration of the First World War, staid Belgrade headily embarking on the jazz age when the war is over, the pinched depression years during which Miss Raika dies. The requisite drama – the testing of the ruling passion – is present in the form of a young man whose physical resemblance to a beloved uncle long dead touches Miss Raika’s heart enough to make her swerve, though only momentarily, from her objective of never parting with her money. The novel is written in 1954. Ćamil, a wealthy young man of Smyrna living in the last years of the Ottoman Empire, is fascinated by the story of Džem, ill-fated brother of the Sultan Bajazet, who ruled Turkey in the fifteenth century. Ćamil, in his isolation, comes to believe that he is Džem, and that he shares his evil destiny: he is born to be a victim of the State. Because of his stories about Džem’s ambitions to overthrow his brother, Ćamil is arrested under suspicion of plotting against the Sultan. He is taken to a prison in Istanbul, where he tells his story, to Petar, a monk.

The novel is written in 1954. Ćamil, a wealthy young man of Smyrna living in the last years of the Ottoman Empire, is fascinated by the story of Džem, ill-fated brother of the Sultan Bajazet, who ruled Turkey in the fifteenth century. Ćamil, in his isolation, comes to believe that he is Džem, and that he shares his evil destiny: he is born to be a victim of the State. Because of his stories about Džem’s ambitions to overthrow his brother, Ćamil is arrested under suspicion of plotting against the Sultan. He is taken to a prison in Istanbul, where he tells his story, to Petar, a monk.

Immediately after his death in 1975, Andrić’s literary executors published, as his fourth novel, a chronicle of Sarajevo called “Omer pasha Latas”, which was seemingly intended by the author to complete his chronicles of Travnik and Višegrad and to render to all three of his childhood cities the homage he felt was their due.

Immediately after his death in 1975, Andrić’s literary executors published, as his fourth novel, a chronicle of Sarajevo called “Omer pasha Latas”, which was seemingly intended by the author to complete his chronicles of Travnik and Višegrad and to render to all three of his childhood cities the homage he felt was their due.