Fragment

translated by Joseph Hitrec, George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London, 1969

(...)

Farther away, in the semi-darkness, Djerzelez was lunging after the last of the Gypsy woman and trying to corner Zemka. He forced himself to run as fast as his legs would carry him and was already gaining on her when she suddenly wheeled left and vanished on the path that led down between the ploughed fields. Djerzelez had not expected so sudden a turn heavy, rigid and drunk as he was, having started running he could not stop. He went over the rounded edge of the slope and ran down the high steep bank toward the brook. At first he managed to stay on his feet, but as the incline grew steeper he lost his balance and tumbled like a log all the way down and into the brook. Feeling wet stones and silt under his hands, he began to pick himself up right away. The glare of the blaze was still in his eyes, but down here it was dark. He scooped some water and cooled his hands and forehead. He sat like this for a long while. The night was wearing on.

After a time he felt chilly and was seized by an unpleasant shiver; collecting himself, he resolved in his fuzzy head to drag himself out of the brook. He clambered up the slope, holding on to grass and bushes, using his knees, bearing more and more to the left where the bank was less steep; and all this he did as in a dream.

After a lengthy and strenuous effort, he found himself on the edge of the meadow, which for some time now had been utterly deserted. It was dark up there. He felt the even, hard ground underfoot and only then gave in to exhaustion. He dropped to his knees, broke his fall with his hands, and felt something warm and soft under him; he had landed on the spot where the haystack had burned down. Nausea stirred in his gorge. Under him, in the heap of black soot, a spark glowed here and there. One could hear the dogs snarling and gnawing at the leftover bones. From one of the pines, a cone tumbled down and rolled toward him. He grinned.

"Stop pelting me, Zemka, you, wildcat-come 'ere!"

Try as he might, he could not collect himself. He remembered he'd wanted to fight someone; he wanted to ask what happened... The night was late, the sky overcast; and there wasn't a soul around him: there was no one to ask, no one to fight with.

(...)

As always when he came face to face with womanly beauty, he at once lost all sense of time and proportion, as well as all understanding of his reality that separated people one from another. Seeing her so young and full like a bunch of grape, he never for an instant doubted his rights; all he had to do was stretch out his hand!

With his right eye screwed his legs apart, he looked on for a second, then chuckled softly and, opening his arms and all but skipping, started toward her. The girl saw him in time, tugged the old man's sleeve and pulled her into the doorway. The lithe and ample movements of the ripe lass filled Djerzelez's eyes with dazzle-then, there was a bang and he saw nothing more except, before his very nose, the broad white surface of the outer door, behind which the lock clicked and the stanchion made a grating sound. And there he stood. On his face remained a ghost of a smile, by then quite meaningless. He turned around.

"See!"

In helpless wonderment, he repeated the foolish word several times, like a man who had accidentally bumped into something.

(...)

Her name was Katinka and she was the doughter of Andrew Poljaš. About her beauty songs were sung all over Bosnia, but to her it was a source of unhappiness. Because of it, men besieged her house, and she dared not to go out. On holidays, she would be led at daybreak to the early mass in the Latin Quarter, shrouded in a big shawl like a Turkish woman so that no one should recognize her. She seldom ventured even into her own courtyard, for right next to it was the military academy, towering above their own house by a whole floor, and the cadets, young men poorly fed and much whipped, spent long hours on the windows, wan with desire, hungrily watching her as she moved around. And whenever she did go down, she would see behind a certain window the leering face of the mad Ali, a yellow-skinned half-wit with missing front teeth, who was a janitor in the academy.

It happened sometimes, after a stormy evening, when the soldier and local lads had whooped and coughed pointedly under her windows and banged on the front door, that her mother would scold her, blameless and upright though she was, and wonder aloud whom she'd "taken after" that the whole town should lose its wits over her and their home invite so much harassment, and the girl would listen to her, buttoning the waistcoat over her breast, without a ray of comprehension in her big eyes. Often she wept all day long, not knowing what to do with her life and with her wicked beauty. She cursed herself and fretted, and struggled vainly in her great innocence to fathom that "brazen and Turkish thing" about her that turned the heads of men and made the soldiers and tramps rut and prowl around her house, and because of which she had to hide and feel ashamed, and her own folk had to live in fear. And she grew more lovely by the day.

From then on, Djerzelez spent all his afternoons in the halvah shop. Several local men began to congregate there too. The young Bakarević also came, and so did Derviš Beg from Širokača, red-haired and bloated with drink, and now, because of the fast, bad-tempered like a lynx to boot; and Advik Krdalija, frail, haggard, and keen like a tongue of fire, a notorious manslayer and lady-killer. Here in the twilit halvah shop where every single thing had tarnished and become sticky from sugar and sweet vapors, they would wait for the cannon shot that announced the breaking of the fast, and would carry on long conversations about women in order to forget their thirst and still their craving tobacco. Djerzelez listened to them, while his parched mouth felt bitter and every muscle twitched with a kind of aching restlessness; he laughed and sometimes joined in their chatter, but was apt to maunder and could not articulate his feelings. And in all that time Katinka's house, with its padlocked door and empty windows, loomed silently before him.

(...)

Djerzelez had known her for some time.

She was taken aback by being visited in broad daylight; she rose to her feet, and he said quietly from the door:

"Yekaterina, here I am."

"Good, good-welcome," she said, meekly setting the bolsters for him.

He lowered himself onto a short cushion, while she remained on her feet, bending a little. Without another word, he began and unbuckle and loosen his clothing.

Afterwards he lay with his head on her lap, while she stroked his sunburned neck. He pressed his face into the thin fabric of her pantaloons; behind his lids there was a steady throbbing of red rings sent up by his hapless blood and a shimmer of countless memories, now blamed and distant.

And this hand he felt on his body, was it the hand of the woman? Of the Venetian wrapped in fur and velvet, whose body, slender and aristocratic, was past imagining? Of the Gypsy Zemka, the bare-faced and crafty yet also loving animal? Of the fat widow? Of the passionate and devious Jewess? Of Katinka, the fruit ripening in the shade? No, it was the hand of Yekatreina. Just Yekaterina's! Yekaterina was the only one a man reached in a straight line!

And once more he pondered a thought with which he'd gone to sleep a hundred times, an unclear thought, never pursued to the end, yet humiliating and depressing: Why was the path to a woman so tortuous and mystifying, and why was he, with all his fame and strength, unable to traverse it, when so many men worse than him did? So many-yet only he, in his vigorous and laughable prime, for ever held out his arms as in a dream. What was it women were after?

The tiny hand did not stop caressing him, deftly and expertly, up and down the spine. And the nightmare thought faded again, settling heavy and unsolved within him. He spoke absently, not moving.

"What a lot of the world I've seen, Yekaterina! How far I've wandered!"

He didn't know whether he meant this as a complaint or a boast; and he caught himself short. He lay quietly in the dreamy silence, in which the days and events of the past overlapped, blended, and made peace with each other. He forced himself to close his eyes, wishing to prolong this moment that was free of thought and desire, to rest as well as he could, like a man for whom a day was only a short pause and who had to resume his journey.

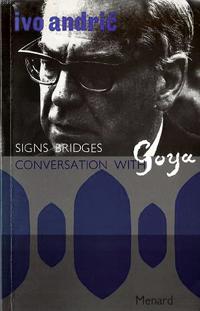

The work which most obviously spans the categories of fact and fiction, history and legend is the “Conversation with Goya” (1935). Here, the author’s identification with his subject is complete. The ideas attributed to Goya are in fact Andrić's own reflections on the nature of art, provoked by an affinity with the painter's work. Had Andrić been interrogated as Ćamil was, he would have had to reply: "I am he".

The work which most obviously spans the categories of fact and fiction, history and legend is the “Conversation with Goya” (1935). Here, the author’s identification with his subject is complete. The ideas attributed to Goya are in fact Andrić's own reflections on the nature of art, provoked by an affinity with the painter's work. Had Andrić been interrogated as Ćamil was, he would have had to reply: "I am he".